AS teenagers growing up in East London in the Sixties and early Seventies, my brothers and I were, I suspect, among very few youngsters in apartheid South Africa who actually listened to and enjoyed Jimi Hendrix’s psychedelic sounds.

But from 1967 till his death from an overdose of sleeping pills in 1970, Hendrix was a sensation in Britain, Europe and the US. And today he is consistently voted by music magazines, musicians and fans as the greatest rock guitarist who every lived.

At the time there was little hope of hearing Hendrix on the SABC’s Springbok Radio hit-parade or general playlist. In order to hear our hero on the air we had to tune into LM Radio, broadcast on shortwave from the Mozambique capital, Lourenzo Marques, now Maputo.

Born Johnny Allen Hendrix in Seattle, Washington on November 27, 1942 – and changed to James Marshall Hendrix in 1946 – Hendrix couldn’t have been more representative of the American people. His antecedents were African, European, Cherokee Indian and Mexican. An unsettled home environment saw him spend much of his early years with his grandmother, a full-blooded Cherokee Indian, in Canada.

Hendrix played for rock and roll teenage bands, but was thrown out of school at the age of 16 – apparently for holding hands with a white girl. In 1959, at the age of 17, he voluntarily enlisted to join the army. Fortunately for rock music, after 14 months as a paratrooper he suffered an injury and was discharged.

As the Swinging Sixties got under way, he decided to devote his life to music. For the next four years he worked around the US, playing backing guitar for various rhythm and blues bands, including Little Richard, Ike and Tina Turner, Wilson Picket, the Isley Brothers and King Curtis.

But he was too much of an individualist for this sort of role, and was eventually drawn to New York’s Greenwich Village, not long after folk-singing guru Bob Dylan had made his mark there.

In late 1965 he formed his first band, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. While working the clubs, his talent was immediately recognised. Former Animals bassist Chas Chandler was so impressed he offered to become his manager, and persuaded him to accompany him back to London.

In the wake of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, a veritable glut of world-class groups had coalesced in the British capital. Among them were some of the greatest guitarists of the time, including Eric Clapton, playing for Cream, and Jimmy Page, with Led Zeppelin. The lead guitarist for The Who, Pete Townshend, was making a name for himself, not only as a great composer and musician, but also for his aggressive stage antics, which included smashing his guitar at the end of live performances.

Into this white-dominated music renaissance enter one wild-haired, left-hand-guitar-playing black guy with a penchant for colourful clothes and a volatile stage temperament. Hendrix teamed up with Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums to form the Jimi Hendrix Experience. He took the UK by storm, creating a wide range of sounds never heard before.

Because he played it left-handed, he held his famous Fender Stratocaster electric guitar with the tuning keys facing downwards, adding another eccentric dimension. It is interesting to note on Wikipedia that he was apparently not left-handed, and used to write with his right hand. Also, because he strung the guitar back to front, the pick-ups were reversed, giving the higher notes a mellower sound and the bass strings a sharper edge. The fact that the tremolo arm and volume control buttons were above the strings made it easier for him to manipulate them. Watching Hendrix on the Woodstock film – when the cameraman manages to focus on his guitar instead of his face! – one gets a feeling for what made him so good. He works that tremolo arm continually, while at the same time picking out the notes with his plectrum. The right-hand-work up and down the fretboard is, naturally, lightning fast. It is as if he is putting together an entire orchestra of electronic sounds virtually single-handed. Listen to any of his albums and that is the effect. On Band Of Gypsys, in particular, you get the feeling that every note and chord and everything that he manages to squeeze in between in terms of fuzz, wah-wah and feedback, is completely under his control and precisely as he intended. To listen to Hendrix at his best is to go beyond the realms of modern popular music, be it rock, blues or jazz, and into an entirely new dimension the likes of which we’ll never experience again. It was for good reason his band was called the Experience, because it was indeed an altogether different, almost surreal, experience.

It was, apparently, Frank Zappa who introduced Hendrix to the wah-wah pedal, which was just a small part of his electronic arsenal. As the Wikipedia chapter on his guitar legacy underscores, he was continually experimenting and improvising in order to push the envelope of the electric guitar sound to its limits. His use of the Marshall power amplifier soon made it de rigeur for all reputable rock bands.

Often stoned on some or other drug, he would exploit the infinite possibilities of feedback, as well as stunning audiences by playing behind his back, above his head and with his teeth.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Under Chandler, who had heard Hendrix play “Hey Joe” in Greenwich Village and invited him to come to the UK, Hendrix teamed up with Redding and Mitchell. As the cover to Are You Experienced shows, their fair “Afro” hairstyles were even larger than Hendrix’s. This alone, set the band apart, giving them an ultra-hip image that I, as a youngster growing up, immediately could relate to. It was the image of Underground music, of music that our parents would NEVER be able to relate to. And, as shown on the cover of Smash Hits (his first compilation album, released in 1968) and in numerous other photos, Hendrix set the tone for hip dressing, making most of the other supposedly cool bands look rather kitsch by comparison.

Smash Hits

Anyway, back then, for me, it was all about the music that this threesome could produce. And, as history records, they had a series of singles which reached the British Top 10, including Hey Joe, Purple Haze and The Wind Cries Mary. Hendrix’s first own composition, Stone Free, was on the B side of Hey Joe. We did not get the first album, Are You Experienced, which was released on May 12, 1967, but it was only kept from No 1 in the UK by the Beatles’ Sgt Peppers album. We got familiar, however, with most of the songs, either through the singles or their inclusion on Smash Hits, released in 1968. (I well recall a visit to the home of a friend in Stirling, East London, at around that time, and listening to Smash Hits while sitting in the gardener’s room at the back of the home. The friend’s father was a wealthy doctor, and was away at the time, so we had something of a jol. I remember the album Chicken Shack was doing the rounds, as well as the long Fleetwood Mac single, Oh Well, which took up two sides. But it was while smoking dope in the dark, back room with the gardener while listening to Hendrix, that someone brought in a tray of lovely pink, newly baked cookies. I was ravenous and ate three quarters of one before discovering they were dagga cookies. This must have been in around 1973, because I think that was my last dagga experience. Unlike inhaled dagga smoke, the ingested stuff stays with you that much longer. It was a bad, bad trip, a real bummer. I thought I might die. I felt like puking all the time and was totally wasted for about 12 hours.)

I had intended starting by looking at Are You Experienced, but decided that Smash Hits, though released after it, in fact effectively precedes it in so far as it contains those pivotal first six songs released on singles.

It is a moot point how Hendrix’s career might have panned out had he not moved to the UK with Chandler, but having just listened to this album afresh, I think we can all be grateful he arrived in London at a time when record producers and engineers were really starting to hone the rock sound to perfection. And they couldn’t have asked for a better musician to perfect their skills on than Hendrix, who clearly had a mind for the wizardry of electronics when it came to making music.

But what does Wikipedia have to say about an album which, to my mind, must have been released with a view to ensuring those six hits were included on an album after their being omitted, from the UK version anyway, of Are You Experienced?

We are told that the UK album was released in April 1968, and the US version in July 1969. Its UK release came four months after the second album, Axis: Bold as Love, and in fact contains their first four hits and their B-sides. I wonder what the fourth hit was? It also has four “standout tracks” from Are You Experienced. And, as Wikipedia notes, Smash Hits became a smash hit, reaching No 5 in the UK. The US version, for reasons such as he had not had any hits there yet and because Are You Experienced already contained several of the UK hits, was a very different album, though it does not include any songs off either Axis and only two off Electric Ladyland. It reached No 6 there. To obviate confusion, in 1997 Experience Hendrix: The Best of Jimi Hendrix was released on CD and is “the definitive Hendrix compilation”, says Wikipedia.

Anyway Smash Hits was the album which we all got into in a big way, and it’s not surprising. While these are all shortish tracks, it is significant that not one passes without at least one substantial lead guitar solo. I also noticed, having just listened to it afresh, that on some songs Hendrix is able to produce at least half a dozen distinct guitar sound variations. Use of the wah-wah pedal obviously was part of the trick, but he did seem to turn the instrument into something which at times sounds altogether alien and new. On each track the guitar is like a glue which binds those incredible drums, bass and vocals together in incredibly tight compositions which to this day, in my experience, have yet to be emulated. Each track opens with a distinctive lead riff, or blaze of heavy chords, and the opening melody on Purple Haze has been immortalised further by its inclusion in the Woodstock set. Remember how some people parodied this superb song by suggesting Hendrix sang, “scuse me while I kiss this guy”. But what precisely did he sing? “Purple haze all in my brain / Lately things just don’t seem the same / Actin’ funny, but I don’t know why / scuse me while I kiss the sky.” Then that surging lead guitar wails the melody – da-da-da, da-da-daa, da-da-da… “Purple haze all around / Don’t know if I’m comin’ up or down / Am I happy or in misery? / What ever it is, that girl put a spell on me.” With his guitar cruising alongside him, he expands on the impact, not it seems of drugs, as everyone suggested, but of a girl. “Help me / Help me / Oh, no, no …” As the song becomes more of an instrumental, a sunburst of sound, Hendrix talk-sings phrases like “Hammerin / Talkin bout heart n ... s-soul / I’m talkin about hard stuff / If everbody’s still around, fluff and ease, if … / So far out my mind / Somethings happening, somethings happening / Ooo, ahhh / Ooo, (click) ahhh, / Ooo, ahhh / Ooo, ahhh, yeah!”. Finally, having given the world one of its first tastes of his genius, he winds up the song with the following: “Purple haze all in my eyes, uhh / Don’t know if its day or night / You got me blowin, blowin my mind / Is it tomorrow, or just the end of time?” Again, the vocal improvisations, which are such an integral part of the Hendrix sound, see out the song, alongside more incredible guitar gymnastics.

Fire, the title of the second song on the album, rang no bells … until I heard the fast-paced opening notes and chords. Alongside some superlative drumming, Hendrix calls for your attention – or at least he addresses his love interest in another classic bit of talking blues. “Alright, / now listen, baby / You don’t care for me / I don’-a care about that / Gotta new fool, ha! / I like it like that / I have only one burning desire / Let me stand next to your fire.” That last line is repeated four more times, with the backing vocalists to the fore, as the guitar weaves its magic path. But this is no time to get laid back man; Jimi has something more to say. “Listen here, baby / and stop acting so crazy / You say your mum ain’t home, / it ain’t my concern, / Just play with me and you won’t get burned / I have only one itching desire / Let me stand next to your fire / Let me stand next to your fire.” The famous Hendrix-as-sex-god thing probably stems from this sort of song, where beautiful girls are invited to “play” with him and not “get burned”. But, as with so many of his songs, there is time now for a mood switch. “Oh! Move over, Rover / and let Jimi take over / Yeah, you know what I’m talking ’bout / Yeah, get on with it, baby / That’s what I’m talking ’bout / Now dig this! / Ha! / Now listen, baby…” It is about here that, over and above the radiant guitar flourishes already heard, he launches into another virtuoso lead solo, before returning the song to its original shape. “You try to gimme your money / you better save it, babe / Save it for your rainy day / I have only one burning desire / Let me stand next to your fire …” Unlike Purple Haze, Fire was not a “smash hit”, but the next song, The Wind Cries Mary, was.

One of the longer tracks on the album at 3:20 minutes, this starts with slow, subtle chords with the cymbals brushed lightly. It would ordinarily be described as a slow blues rock sound, I suppose, but then of course it was impossible to categorise Hendrix in this way. Because in the end there is only one song of this nature in the world, and this is it. It also happens to contains some of Hendrix’s finest whimsical lyric-writing. “After all the jacks are in their boxes /And the clowns have all gone to bed / You can hear happiness staggering on down the street / Footsteps dressed in red / And the wind whispers Mary.” The lead guitar magic woven here is impossible to describe. Hendrix is one musician whose virtuosity, whose all-consuming genius, is impossible to do justice to in the written word. But it was also hung on some superb lyrics, the likes of which Dylan probably envied. “A broom is drearily sweeping / Up the broken pieces of yesterdays life / Somewhere a queen is weeping / Somewhere a king has no wife / And the wind, it cries Mary.” And as the tension increases, with the wind first whispering, now crying, and next screaming, so too does the mood of the song tauten. I loved the next line. “The traffic lights, they turn, uh, blue tomorrow / And shine their emptiness down on my bed / The tiny island sags down stream / cause the life that lived, / Is dead / And the wind screams Mary.” This stands as a brilliant poem in its own right. Couched in Hendrix’s musical cloak, it becomes a thing of the finest beauty. “Uh-will the wind ever remember / The names it has blown in the past? / And with this crutch, its old age, and its wisdom / It whispers no, this will be the last / And the wind cries Mary.” And so the music, like the wind, gradually subsides.

Fittingly, this is followed by a pulsating, up-tempo track, Can You See Me, which also relies on regular halts and changes of pace. It is here that I detected about half a dozen different guitar “textures”, different qualities of sound all generated by that Hendrix guitar. “Can you see me? begging you on my knees / Wo yeah / Can you see me baby / Baby please don’t leave / Yeah if you can see me doing that / You can see in the future of a thousand years.” Then that wacky guitar riff which no one, but no one, will ever play again precisely like Hendrix did – da-da-daa-da, da-du-du-du-du-du, wheeeeeaaah. “Can you hear me? / Cryin’ all over town / Yeah babe / Can you hear me baby? / Crying cause you put me down / What’s with ya / If you can hear me doing that / You can hear a freight train coming from a thousand miles.” It is a classic blues-rock, given the full Hendrix treatment. “Ah yeah / Can you hear me? / Singing this song to you / Ah you better hold up your ears / Can you see me baby? / Singing this song to you / Ah shucks / If you can hear me sing / You better come home like you supposed to do.” Naturally there is an incredible lead solo amidst all the other lead guitarwork before he winds the thing down. “Can you see me? / Hey hey / I don’t believe you can see me / Wo yeah / Can you hear me baby? / I don’t believe you can / You can’t see me.” Hendrix was one sensitive soul. And here we perhaps get a glimpse into how he is confronted by rejection. This is a cry of love from a man who is hurting bad (as they say). That song was not a hit single, but the next track, 51st Anniversary was, albeit on the B-side to Purple Haze.

At a time when we, as youth, were totally intolerant of our parents’ ageing generation, I always saw this song as taking a dig at the old toppies, even those who would have been our grandparents’ age.

Okay so I was wrong all those years ago. The song does not conform to normal English grammar and say “for fifty years…”. No, starting with some steady rhythm guitar and then the melody picked out on lead guitar as only Jimi can, the first verse reads: “A fifty years they’ve been married / And they can’t wait for their fifty first to roll around / Yeah, roll around.” The lead and bass guitars indulge in some complex interplay before the couple seem to lose a few decades. “A thirty years they’ve been married / And now they’re old and happy and they settle down / Settle down yeah!” Then, 10 years earlier, “Twenty years they’ve been married / And they did everything that could be done / You know their havin’ fun.” But this is just setting the scene, because at this point, that guitar leads one to another plain, with a slower, more studied beat. “And then you come along and talk about / So you say you wanna be married / I’m gonna change your mind.” Everything unwinds and unravels as he continues. “Oh got to change / That was the good side baby / Here comes the bad side.” This next verse I can’t recall at all, but it offers pause for thought. “Ten years they’ve been married / And a thousand kids run around hungry / Cause ther mother’s a louse / Daddy’s down at the whiskey house / That ain’t all.” And there is another equally sour side to marriage: “For thirty years they’ve been married / They don’t get along so good / They’re tired of each other, you know how that goes / She got another lover / Huh same old thing.” He then addresses this girl: “So now you’re seventeen / Running around hanging out, and a havin’ your fun / Life for you has just begun, baby.” Again, we move to that rarified plain, where, with a few sniffs, Hendrix addresses her again. “And then you come saying / So you, you say you wanna get married / Oh baby trying to put me on a chain / Ain’t that some shame / You must be losing your (Sniff), sweet little mind / I ain’t ready yet, baby, I ain’t ready / I’m gonna change your mind.” Those descending notes plunge the song into its end zone as Hendrix lets the guitar explore a phalanx of emotions while chanting things like “Oooh look out baby / Oh / I ain’t ready / I ain’t ready / I ain’t ready”. Later on, in words that would soon contain a tragic poignancy, he adds: “Let me live / Let me live / Let me live a little longer …”

The final track on Side 1, Hey Joe, was naturally a smash hit. Written by Billy Roberts, it opens with a lead guitar riff that has become virtually an emblem of the rock era: daa-daa-da-da-daa. It is little more than a slow blues, but again in Hendrix’s hands, backed it must be said by the incredible musicianship of Redding on bass and Mitchell on drums, this became an iconic moment in the history of rock music. Superb backing vocals and a lead guitar solo that would set the standard for all time, Hendrix was making music that, in a sense, spelt the end of rock music. There would be all manner of interesting sounds after Hendrix, but never again one talent as unique and special. At 3:30 minutes, it is a relatively long song for a hit single, but it passes in a flash. With those backing vocals ooing on each line, he launches into the lyrics. “Hey Joe, where you goin’ with that gun in your hand? / Hey Joe, I said where you goin’ with that gun in your hand? / Alright. I’m goin down to shoot my old lady, / you know I caught her messin’ ’round with another man. / Yeah,! I’m goin’ down to shoot my old lady, / you know I caught her messin’ ’round with another man. / Huh! And that ain’t too cool.” It is, of course, a violent song, but such was the effect that such affairs of the heart could have on a man. In the second verse, the backing vocalists sing “Ah” as he continues. “Uh, hey Joe, I heard you shot your woman down, you shot her down. / Uh, hey Joe, I heard you shot you old lady down, / you shot her down to the ground. Yeah!” Joe responds: “Yes, I did, I shot her, / you know I caught her messin’ ’round, / messin’ ’round town. / Uh, yes I did, I shot her / you know I caught my old lady messin’ ’round town. / And I gave her the gun and I shot her!” After that lead guitar clears the cobwebs, the verses become short, clipped lines about Joe and his future. Things like “where you gonna run to now”, to which he replies that “I’m goin’ way down south, way down south, / (Hey) /way down south to Mexico way! Alright! / (Joe) / I’m goin' way down south, (Hey, Joe) / way down where I can be free! / (where you gonna ...) / Ain’t no one gonna find me babe! / (... go?) / Ain’t no hangman gonna, / (Hey, Joe) / he ain’t gonna put a rope around me!..” And so the song winds down with more ad-libbing. It was a tour de force, but then again just one of oh so many by the master.

The incredible urgency that Hendrix was able to inject into a song is evident in Stone Free, which was a B side on one of those early hit singles. Playing both rhythm guitar and those sudden lead riffs, Hendrix gets this one soaring straight away, helped in no small measure by Mitch Mitchell’s jazzy drumming and Noel Redding’s exceptional bass, which really held each song together. “Everyday in the week I’m in a different city / If I stay too long people try to pull me down / They talk about me like a dog / Talkin’ about the clothes I wear / But they don’t realise they’re the ones who’s square.” He’s up and running, on a roll, as it were. “Yeah! / And that’s why / You can’t hold me down / I don’t want to be tied down I gotta move / Hey.” This seems to be a recurring Hendrix theme – the need not to be tied down to one relationship. The chorus follows: “I said / Stone free do what I please / Stone free to ride the breeze / Stone free, baby I can’t stay / I got to got to got to get away / Yeah.” And this is the first time, reading these lyrics, that I’m picking up on what he was singing about. The next verse follows the same theme. “Listen here baby / A woman here a woman there try to keep me in a plastic cage / But they don’t realise it’s so easy to break / Yeah but a sometimes I get a ha / Feel my heart kind a getting’ hot / That’s when I got to move before I get caught.” After saying “So dig this” he unleashes a short but scathing lead guitar assault, before returning to that chorus. “And that’s why, listen to me baby, you can’t hold me down / I don’t want to be tied down / I gotta move on / I said / Stone free do what I please …” And so, as the lyrics are repeated, he opens space for some of that distinctive improvisation which is usually a combination of vocals and lead guitar, not to mention in this case some wonderful changes of tempo, with the bass guitar up there in the thick of things.

The Stars That Play With Laughing Sam’s Dice was a B side on one of those hit singles, and is a fine early example of the sort of surreal soundscapes Hendrix became so adept at creating. It starts off fairly low-key, with Hendrix’s vocals somewhat muted. “The stars up above that play with Laughing Sam’s dice / They make us feel the world was made for us / The zodiac glass that beams come through the skies / It will happen soon, for you.” Of course I always heard the tune and the shape of the sentences, but this again is the first time I’m seeing these lyrics. After that opening verse, Hendrix kicks that wah-wah pedal into life, taking one into a different world, or indeed into space. Here he talk-sings his way along a weird audio journey, whilst always retaining an understated sense of humour. “And away we go / Yeah / Thank you very much / Thank you very much / And now we would like to bring to you our wide lonely friendly neighborhood / Experience me / Right now listen / The Milky Way Express is loaded, all aboard / I promise each and every one of you, you won’t be bored / What I’m really concerned about / Is my brand-new pair of butterfly roller skates / Thank you, thank you.” As he explores the gamut of sound possibilities on his guitar, still in the roll of space ship tour guide, he continues: “No throwing cigarette butts out the window / No throwing cigarette butts out the window / Now if you look to your right you’ll see Saturn / If you look to the left you’ll see Mars / I hope your brought your parachutes with you / Hey look out! / Look out for that door / Don’t open that door / Don’t open that door / Oh well / That’s the way it goes / Hey, everything is all right now.” I recall him concluding with the words, “I hope you’re enjoying your trip / I am …”

First, a cluster of chords, then some quickfire rhythm sets in as Manic Depression gets under way, with Hendrix singing those lyrics which, for the main part, I think I actually heard in my youth. “Manic Depression / touching my soul, / I know what I want, / but I just don’t know how to go about getting it.” His voice lowers: “Feeling, sweet feeling / drops from my finger, fingers / Manic Depression’s captured my soul.” Fortunately for us, at the time we had little idea of what this condition was all about, and I’m not sure the term wasn’t used here more for effect that anything else. Again, the sound is ever so tight, with the lead and bass overlapping beautifully. “Woman so willing the sweet cause in vain, / you make love, / you break love, / it’s-a all the same when it’s ... / when it’s over.” Then: “Music sweet music, / I wish I could caress, caress, caress. / Manic Depression’s a frustrating mess.” He then tries to get a hold of himself. “Well, I think I’ll go turn myself off an’ go on down. / Really ain’t no use me hanging around. / Oh, I gotta see you.” In the midst of that is a lead solo featuring extensive feedback, played at breakneck speed, as he explores the furthest reaches of what is possible on the instrument. There is also a great “duel” between the guitar and Mitchell’s drums. So much, indeed, packaged in 3:42 minutes of music.

What is with this Chile thing. It is a word that Hendrix seems to use interchangeably with Child. Anyway, Highway Chile was a B side on one of those early hit singles, and it starts with searing lead guitar notes: daa da-da da-da-daa, daa da-da da da-daa. Immediately you have that laid down, it is as if the song is preordained. Everything just gels around it. And, of course, again I did not get all the lyrics, so it’s great finally to be introduced to them. “Yeah, his guitar slung across his back / His dusty boots is his Cadillac / Flamin’ hair just a blowin’ in the wind / Ain’t seen a bed in so long it’s a sin / He left home when he was seventeen / The rest of the world he had longed to see / But everybody knows the boss / A rolling stone who gathers no moss.” This is great poetry, and one suspects, fairly autobiographical. The tension ratchets up. “But you’d probably call him a tramp / But it goes a little deeper than that / He’s a highway chile, yeah.” The song halts briefly as that opening riff is injected ahead of the words, “highway chile”, before the narrative continues. “Now some people say he had a girl back home / Who messed around and did him pretty wrong / They tell me it kinda hurt him bad / Kinda made him feel pretty sad / I couldn’t say what went through his mind / Anyway, he left the world behind / But everybody knows the same old story, / In love and war you can’t lose in glory / Now you’d probably call him a tramp / But I know it goes a little deeper than that / He’s a highway chile…” Again, Hendrix starts to ad lib with things like “Walk on brother, yeah / One more brother”, as the space for some more lead guitar exploits is created.

While again, a B side of those early hits, The Burning Of The Midlight Lamp is one of Hendrix’s great phsychedlic songs, which fittingly starts with a guitar, wah-wah in full force, that sounds like a mixture of a harpsichord and pure electronic sound forces, which somehow emanate from a guitar, via an array of unfathomable gizmos. Yet Hendrix seemed to have absolute control over what he was doing, what sound he wanted to make. “The morning is dead / And the day is, too / There’s nothing left here to meet me / But the velvet moon / All my loneliness I have felt today / It’s like a little more than enough / To make a man throw himself away.” This runs straight into the chorus. “And I continue / To burn the midnight lamp / alone.” This is possibly the first time on a single that Hendrix really got his guitar to talk, the wah-wah effect being used to create an alien sound such as had arguably never been heard before on this planet. Yet, at times, the song is simply a slow blues, but with altogether new layers of sound and texture. “Now the smiling portrait of you / Is still hangin’ on my frowning wall / It really doesn't, really doesn’t bother me too much at all / It’s just the ever falling dust / That makes it so hard for me to see / That forgotten earring layin’ on the floor / Facing coldly towards the door.” What brilliant writing! Again, these words were never fully heard, so here we see Hendrix’s ability to use all manner of grammatical devices, including transferred epithets with that frowning wall and the earring facing coldly towards the door. Anyway, after the chorus is repeated, he concludes that “Loneliness is such a drag”, before that guitar/harpsichord reverberates its sound prior to the next verse. “So here I sit to face / That same old fire place / Getting’ ready for the same old explosion / Goin’ through my mind / And soon enough time will tell, / About the circus in the wishing well / And someone who will buy and sell for me / Someone to toll my bell.” I always heard “circus AND the wishing well”, but having one in a wishing well is just that much more bizarre. Anyway, as again he lets the guitar bubble and squeak, wail and whimper, Hendrix resigns himself to his fate: “But I continue / To burn the midnight lamp / Lord, alone / Darlin’ can’t ya hear me callin’ you? / So lonely / Gonna have to blow my mind / Lonely …” If these words remotely reflect what emotions he personally was going through, it is small wonder he struggled to find peace on this earth.

Another side of Hendrix, the charming womanizer, seems to pour forth on the last track on Smash Hits, Foxy Lady, which surprisingly was not among those initial hit singles. Yet it is one of his most famous songs, and features one of the most instantly recognisable opening lead guitar salvoes in the history of rock. With the word “Foxy” chanted by the backing vocalists, Hendrix lays it on the line: “You know you’re a cute little heartbreaker / Foxy / You know you’re a sweet little lovemaker / Foxy.” Then that famous chorus. “I wanna take you home / I won’t do you no harm, no / You’ve got to be all mine, all mine / Ooh, foxy lady.” Probably one of his most famous live acts, Hendrix really hams it up on this song, the guitar textures rich and sensual. “I see you, heh, on down on the scene / Foxy / You make me wanna get up and scream / Foxy / Ah, baby listen now / I’ve made up my mind / I’m tired of wasting all my precious time / You’ve got to be all mine, all mine / Foxy lady / Here I come.” Of course this is the signal for another Hendrix lead guitar assault as he again improvises and talk-sings his way to its conclusion.

Never before had anyone made sounds like these. Little were we to know that it would be a one-off. No one has come close, and this was just the first taste, the short singles. What was to come on later albums, from his live antics on stage, to the incredible effects he achieved in the studio, would blow our minds. Interestingly, I notice that Wikipedia credits Hendrix with playing bass and piano as well as his lead guitar and vocals on this. No doubt he put the piano through an electronic device which convinced me I was hearing a guitar, or harpsichord, or whatever. With this guy you were often just left scratching your head, marvelling at what he was producing.

Are You Experienced

So much for Smash Hits, which was, of course, not Hendrix’s first album. Wikipedia tells us his debut album, Are You Experienced, was released on May 12, 1967, in the UK and three months later in the US and Canada. Produced by Chandler, it was recorded in London between October 26, 1966, and April 3, 1967, and Wikipedia classifies it as “hard rock, psychedelic rock, blues-rock” and says the album “highlighted (his) R&B-based psychedelic, feedback-laden electric guitar playing, and launched him as a major new international star”. In 2005, the album was selected for permanent preservation in the US National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress.

It is sobering to think that it was as far back as September 1966 that Chandler took Hendrix over to England with him, where they formed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Track Records, newly formed by The Who’s managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, signed the group, although their debut single appeared on Polydor Records because Track was not yet up and running. It was in late 1966 and early 1967, says Wikipedia, that Chandler produced their “three classic Top 10 hit UK singles”. Hey Joe/Stone Free was released in December 1966, Purple Haze/51st Anniversary in March 1967 and The Wind Cries Mary/Highway Chile in May of that year. All, as mentioned earlier, featured on the UK version of Smash Hits. Wikipedia says while making these singles, other tracks were cut for their debut album. Eddie Kramer was the Olympic Studios engineer. As happened with other bands, including The Who, Are You Experienced, which was released in May 1967, did not include the three hit singles because that was “the custom in the UK at the time”. Despite that, Are You Experienced, and Hendrix, “became a sensation all across Europe, with the album reaching No 2 in the UK behind the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Not a bad debut!

I was initially going to overlook a paragraph on the cover variations across Europe, but noticed that Wikipedia includes a section about the South African Polydor release. It says that “obviously due to the apartheid racial barrier, and that the main customer base was seen to be ‘whites’, (the album cover) had no pictures, only text on a plain red background (mono only)”. Does that mean they wanted to pretend Hendrix wasn’t black? Such was our absurdity, our infamy. The likes of Australia, New Zealand and Japan used the original UK layout.

But what of the US? Wikipedia says it was “only after the band’s show-stealing performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967 that his USA and Canada label, Reprise Records, prepared the album for release, but with some significant changes”. It says a more psychedelic design was devised by photographer Karl Ferris. And three songs, Red House, Can You See Me and Remember, were removed to make way for the three UK hit singles. Hendrix, says Wikipedia, was not happy with the omission of Red House, supposedly on the pretext that the US and Latin America did “not like the blues”. A plus, however, was that the songs were remixed into stereo for the US pressing. Such was the album’s success that Axis: Bold as Love, released in the UK that December, was held over for six weeks in the US, where it finally reached its peak of No 5 in October 1968.

Are You Experienced, says Wikipedia, “has been cited as one of the greatest debut albums of the rock era”. The 2003 Rolling Stone magazine list of the 500 greatest albums of all time ranked it at number 15.

As we never had this album, I don’t have specific memories about the track listing, but a cursory look at the song titles reveals that I know virtually all the songs. These were heard either on LM Radio or seven singles, but most likely on various compilation albums from the early 1970s and, of course, on Smash Hits, which was a coveted album among the small group of us in East London who gravitated to this sort of music. As noted earlier, all six of the songs on those first three singles are on Smash Hits - Hey Joe, Stone Free, Purple Haze, 51st Anniversary, The Wind Cries Mary and Highway Chile – with four drawn from Are You Experienced, namely Can You see Me, Manic Depression, Fire and Foxy Lady. I also picked up a treasured South African compilation audio cassette, Masters of Rock: Jimi Hendrix, which fills in a few of the remaining gaps, including Are You Experienced and Third Stone From The Sun.

So, from Side 1, I have already looked at the opening track, Foxy Lady, track 2 (Manic Depression) and track 4 (Can You See Me). That leaves Red House (track 3, which is on the Masters of Rock tape), Love Or Confusion (No 5) and I Don’t Live Today (No 6). From Side 2, I don’t recall the opening track, May This Be Love, while Fire has been covered on Smash Hits. 3rd Stone From The Sun is on that Masters of Rock tape, but not Remember, the next track. However, the final track, Are You Experienced, is also on it. So let’s give those tracks a fresh listen and try to get a feel for this album.

Nothing. Nothing I have covered so far. Not one of the brilliant rock groups who burst upon the scene in the mid to late 1960s come anywhere close to achieving what Hendrix achieved in terms of bursting open the envelope and unleashing a range of sounds never, ever, to be repeated. And those three tracks from the debut album, on top of the brilliant tracks already looked at on Smash Hits, underscore the fact that this was indeed one of the most ground-breaking debut albums of all time.

Red House, omitted from the US version because the kids there supposedly weren’t into the blues (it’s the home of the blues, dammit!) has to rank as one of the all-time, if not the greatest, blues numbers ever produced. Not only was Hendrix a natural blues singer, his guitarwork gave him the added advantage of transcending genres, so a blues song becomes far more than that. Red House opens with some weirdly sliding lead guitar, then piercing notes which descend to gel with the bass, as a slow blues is set in motion. With Hendrix affirming the sound with the occasional “yeah!”, he pierces the air with short, penetrating lead breaks, before the song settles for that opening line. “There’s a Red House over yonder / That’s where my baby stays / There’s a Red House over yonder, baby / That’s where my baby stays.” This is followed immediately by: “Well, I ain’t been home to see my baby, / in ninety nine and one half days.” As an aside he says “’Bout time I see her”, before he adds, with a sense of urgency: “Wait a minute something’s wrong here / The key won’t unlock the door.” With the lead guitar, sans any feedback or other gimmicks, pouring forth its virtuous vitriol, an unsettled Hendrix ponders his plight. “Wait a minute something’s wrong baby, / Lord, have mercy, this key won’t unlock this door, / something’s goin’ on here. / I have a bad bad feeling / that my baby don’t live here no more.” But is he that distraught? Uh-uh. As a blues guitarist, he has one thing he can depend on. “That’s all right, I still got my guitar / Look out now …” And, naturally, that “warning” precipitates another virtuoso series of riffs on the guitar. I always loved, even as a teen, his use of the word “yonder”, which is actually very old-fashioned. “I might as well go on back down / go back ’cross yonder over the hill / I might as well go back over yonder / way back over yonder ’cross the hill, / (That’s where I came from.)” And, ever the ladies’ man, he knows just what it is he wants as the song ends in another flurry of lead guitar. “’Cause if my baby don’t love me no more, / I know her sister will!” A few self-satisfied chuckles can be heard as the song concludes.

But it is not Red House which made me believe this was such a ground-breaking album, great, brilliant, though that song is. No, it is 3rd Stone From The Sun which, probably more than any composition, placed Hendrix at the top of the pile in terms of innovative creativity. And to think he conceived and executed this on that debut album. At 6:50 minutes, this is his first real foray into music not somehow, even if subliminally, aimed at a commercial market. Here, for the first time, Hendrix creates an entirely new world, although he had already achieved something of that ambience on The Stars That Play With Laughing Sam’s Dice. But here he takes things to an even higher plain, or is that plane? Certainly, we are again airborne, with our planet, the third “stone” from the sun, clearly the object of his concern. But what was this song all about? Well, firstly, all manner of electronic wizardry, most of it connected to that guitar of his, ensures that we have a song so richly textured it defies description. The slowly strummed opening chords are overlayed with alien-sounding vocals which seem to gnaw away at the sound fabric surrounding them. Gradually, a complex melody coalesces, building steadily to a main theme, which he returns to regularly, despite various lengthy interludes where one diverges from the flight plan. All the time, a kind of celestial wind seems to blow through you, as you join him on this incredible journey. One lyric website tells us that the opening vocals sound so weird because they were slowed down, but insists that with the following lyrics in front of one, “you can understand them!”. So, according to that site, those opening, alien sounds in fact say the following: “ ‘Star fleet to scout ship, please give your position. Over’ / ‘I am in orbit around the third planet from the star called the sun. over’ / ‘You mean it’s the earth? over.’ / Positive. It is known to have some form of intelligent species. Over’ / ‘I think we should take a look.’” Phew! So this is in fact an invasion by aliens. And those vocals, spoken at what is possible a tenth of actual speed, are so convincingly extraterrestrial one should have made that deduction ages ago. But, thanks to that diligent Hendrixphile, we now know. What you do hear, as they approach Earth, are words that sound like “warm, strange warm”, and a melody which, to me, seems to “say” something like “…all we are saying … is give peace a chance … give peace a chance…” An almost conventional lead break heralds the actual opening lyrics, which are spoken-sung: “Strange beautiful grass of green / With your majestic silken seas / Your mysterious mountains / I wish to see closer / May I land my kinky machine.” So this is no ordinary alien. He has a penchant for poetic description, and flies a kinky craft. “Although your world wonders me / With you majestic superior crackling hen / Your people I do not understand / So to you I wish to put an end / And you’ll never hear surf music again …” Ouch! It didn’t take long to displease him. I wonder what that “majestic superior crackling hen” was. I never heard that line before, or the fact that because he did not understand the people, he wished to put an end to them. What we did hear was the line that we would “never hear surf music again”. Having grown up within the sound of the surf at Bonza Bay, East London, and having basically spent my youth swimming in said ocean, where many others surfed on boards, this was, despite its foreboding tone, nonetheless a significant affirmation of the sea’s importance in the greater scheme of things. But, having cast his judgment, Hendrix then unleashes some of the most incredible sounds ever recorded. He at times puts on the brakes, with a crash of chords, then takes one floating through a tranquil deep space before letting loose sounds which somehow combine the neighing of a horse and the trumpeting of an elephant. The apocalypse is now, and as the theme tune returns, thick with distortion and feedback, we float to a dizzying conclusion. As I said, never, ever, to be replicated.

The title track, which concludes the album, while not a letdown – and I must stress that I’m not hearing it now in the sequence it was intended – cannot compete with 3rd Stone in terms of pure inventiveness. But Are You Experienced offers something fresh, what I call the “chucka-chucka” sound, a sort of thickly textured rhythm guitar sound created, I suspect, by resting the fingers lightly across the guitar strings while strumming them. This sets up a steady rhythm which lasts virtually the entire song, over which other guitar sounds are placed, along of course with those spoken-sung lyrics. “If you can just get your mind together / Then come on across to me / We’ll hold hands and then we’ll watch the sunrise / From the bottom of the sea.” Was it the sun that was to rise from the bottom of the sea, or were they watching from there? Nice bit of ambiguity. And so to the chorus, which coincides with some intense chucka-chucka sounds: “But first, are you experienced? / Have you ever been experienced? / Well, I have.” This is followed with: “I know, I know you probably scream and cry / That your little world won’t let you go / But who in your measly little world / Are you trying to prove that / You’re made out of gold and, eh, can’t be sold.” After repeating that he is experienced, he says “Let me prove you ...”, which heralds more guitar pyrotechnics. Then another bit of poetry: “Trumpets and violins I can hear in the distance / I think they’re calling our names / Maybe now you can’t hear them, but you will / If you just take hold of my hand / Oh, but are you experienced? / Have you ever been experienced? / Not necessarily stoned, but beautiful ...” Masterful. Another ground-breaking track.

There are two tracks on this album which I don’t seem to have anywhere on a recording, but which were an integral part of my upbringing. I can still hear them in my mind, but let’s look at the lyrics, which I only ever partially heared. I Don’t Live Today, tragically, seemed to predict his untimely death. “Will I live tomorrow? / Well, I just can’t say / Will I live tomorrow? / Well, I just can’t say / But I know for sure / I don’t live today.” It is a bleak assessment of life. “No sun comin’ through my windows / Feel like I’m livin’ at the bottom of a grave / No-ho sun comin’ through my windows / Feel like I’m livin’ at the bottom of a grave / I wish you’d hurry up and rescue me / So I can be on my miserable way.” Is that a call to a higher power to take him away? He is even more emphatic in the chorus: “(Well), I don’t / Live today / Maybe tomorrow, I just can’t say, but, uh / I don’t / Live today / It’s such a shame to waste your time away like this / Existing …” These lines are repeated as the song winds down in typical Hendrix fashion. He includes coughs and sniffs, as well as calls to “get experienced”.

Love Or Confusion seemed, at the time, to sum up how many adolescents felt when exploring this dodgy subject. Again, only the chorus really caught my attention at the time, so let’s see what the rest of the song says. “Is that the stars in the sky or is it raining far from now? / Will it burn me if I touch the sun, / so big, so round? / Will I be truthful, yeah, / in choosing you as the one for me?” The chorus goes simply: “Is this love baby, / or is it-a just confusion?” The remaining two verses reinforce this sense of, well, confusion. “Oh, my mind is so mixed up, goin’ round ’n’ round - / Must there be all these colours without names, without sounds? / My heart burns with feelin’ but / Oh! but my mind is cold and reeling.” After again asking the question, “Is this love, baby / or is it confusion?”, the song concludes with the lines: “Oh, my head is pounding pounding / going ’round and ’round and ’round and ’round. / Must there always be these colours?” Would that I could hear and experience these two tracks again.

Wikipedia does give a little information about this album, including the fact that Hendrix provides the voice of “Star Fleet” on 3rd Stone, while producer Chas Chandler does the voice of “Scout Ship” on the same song. One should, I believe, also not underestimate the role played by the backroom boys in producing the sounds achieved here. I’m sure they would have some interesting tales to tell about how 3rd Stone was achieved.

Monterey Pop Festival

It was apparently Paul McCartney who recommended to the organisers of the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 that Hendrix be included. Filmed by D A Pennebaker, this concert cemented Hendrix’s fame in the US, especially after his smashing and burning of his guitar during the performance. Having just recently watched Rainbow Bridge, which I taped off the TV, I was intrigued to watch those snatches of Hendrix playing in a garish orange outfit with large ruffed collar. I’m no fashion fundi, but I did find it a trifle over the top. Nonetheless, Hendrix delivered the goods by playing out of his skin and also doing all the tricks on stage which made him both famous and infamous.

I have long contended that Eric Burdon and the Animals were one of the great blues outfits of the sixties, and the fact that Burdon befriended Hendrix in the UK emphasizes the fact that he was part of the pioneering group of musicians of that era who blazed a trail of musical glory. On the album, The Twain Shall Meet, Burdon’s song about the Monterey festival contains the line: “Jimi Hendrix, baby believe me, set the world on fire”. And sometimes his guitar, as well.

Anyway, after touring the UK and Europe, where he honed his stage act, Wikipedia tells of how, on his return to the US, Hendrix played a gig at which Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Brian Epstein, Eric Clapton, Spencer Davis and Jack Bruce were in attendance. He stunned them by doing a reworking of the title track of the famous Beatles album, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

But it is my belief that much of this gimmickry was alien to the real Hendrix, whose more sensitive side is evident in the five albums he recorded - and in the mystical imagery of his startling, colourful lyrics. I recall Hendrix was once quoted as saying he did not enjoy singing much, but that it was a prerequisite for rock success. However, anyone listening to the albums and live acts will realise that he uses his voice as another instrument. With his continual background banter, it is the perfect foil to his virtuoso guitar-work. And so, let’s have an in-depth look at those other seminal albums.

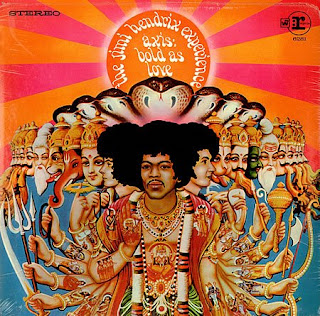

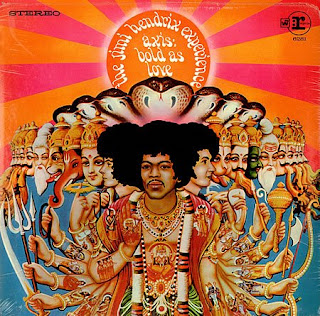

Axis: Bold as Love

Axis: Bold as Love (released in December, 1967 in the UK) was the first Hendrix album we really got into in a big way. Since the art on the cover of records also fascinated me, I was interested to discover on Wikipedia that this cover arose due to a misunderstanding. The British art designers were evidently asked to create a cover incorporating Hendrix’s “Indian” heritage. They did not realise this meant Native American Indian, so the cover ended up with Hendrix and his bandmates as Hindu deities, with multiple hands and serpents towering over their heads. Of course this only added to the Hendrix mystique.

But really, this, for us, was the big one. The album was a constant on our turntable for years and years. Let’s see what Wikipedia has to say about it.

Firstly, it was recorded in May, June and October 1967 at Olympic Studios in London and released on December 1 that year in the UK and January 15, 1968, in the US. Wikipedia calls it blues rock, psychedelic rock, acid rock and hard rock, thereby covering virtually all their bases. It ran to just 38:49 minutes. But what magic was to be found in that short period of time! The tragedy though, for me, is that I don’t have a copy of the album today. I only have some of the songs dotted around on compilation discs and the like. Anyway, the album is pretty well embedded in my soul, so I’ll try to make do.

Produced by Chas Chandler, Axis: Bold as Love was meant to capitalise on the success of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s successful debut album, Are You Experienced. And didn’t it just? It reached No 5 in the UK and an even more impressive No 3 in the US. Wikipedia quotes bassist Noel Redding as saying this was his favourite of the three Experience albums. Interestingly, he plays eight-string bass on some tracks. And tragedy struck just before the album’s release. Wikipedia says Hendrix left the master tapes of Side 1 in a taxi – would you believe! The A-side had to be mixed again in a hurry. And somewhere a London cabby is sitting on a goldmine. How good do you have to be to reach the top? Incredibly, Axis was only ranked No 82 on Rolling Stone magazine’s 2003 list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

But what of the album itself? Key, it seems, was the alchemy which Hendrix and the backup technical people achieved in the studio. Wikipedia says many of the songs were “composed with studio recording techniques in mind and as a result were rarely performed live”. Exceptions were Little Wing and Spanish Castle Magic, the lyrics for which were “inspired by ‘The Spanish Castle’, a dance hall in what is now Des Moines, Washington, near Seattle where Hendrix jammed with local rock groups during his high school years”.

We’ll look out for these things when we listen to the tracks which I have, but Wikipedia tells us that on Little Wing for the first time Hendrix plays his guitar through a Leslie speaker, which is a “revolving speaker which creates a wavering effect, that is typically used with electric organs”. Oh, and Hendrix had an “effects man”. Yes, Roger Mayer, Wikipedia tells us, “then invented the Univibe effects pedal to simulate the Leslie sound” for Hendrix. This was different, it seems, to a commercially sold Uni-Vibe pedal, which Hendrix started using in the summer of 1969. For the techno junkies, Hendrix also used “the obscure and elusive Jax Vibra Chorus – basically a Uni-Vibe with the addition of tremolo and full/slow repeat time selector – on various recordings”. So that goes some way to explaining how a guy who, when he performs, seems to look as spaced out as they come, somehow manages to know precisely what sound he is going to produce every step of the way.

The album starts with EXP, a bizarre radio-type discussion about “the dodgy subject of are there or are there not UFOs”, or suchlike. Wikipedia notes that it starts with a few notes from Stone Free, played “one-half step down” – which presumably means slower. A plethora of incredible sounds leads into the discussion which, I see, is between Mitchell and Hendrix. Mitchell “plays a radio host, and Hendrix plays an outerspace alien in the guise of a human named Mr Paul Caruso, whose voice is gradually slowed down until he eventually takes off in his spaceship, much to the host’s consternation”. Let’s see if we have that discussion on the Web? Indeed we do. The Mitch Mitchell character is the announcer who says: “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. / Welcome to radio station EXP. / Tonight we are featuring an interview with a very peculiar looking gentleman who goes by the name of Mr Paul Coruso on the dodgy subject of are there or are there not flying saucers, or UFOs? / Please Mr Coruso, could you give us your regarded opinion on this nonsense about spaceships and even space people?” At the mention of “even space people”, his voice rises incredulously. Then the languid Hendrix character (Mr Coruso) replies: “Thank you. As you well know you just can’t believe everything you see and hear, can you? / Now, if you’ll excuse me, I must be on my way.” At this point he ascends, leaving the announcer to mumble: “Bu ... but, but ... gulb ... I, I don’t believe it!” Mr Coruso departs with a series of Hendrix special effects: “Pffffttt!! ... Pop!! ... Bang!!” But who was Coruso? Wikipedia says he was a friend of Hendrix’s from his Greenwich Village days, who ended up playing harmonica on My Friend, which was recorded during the Electric Ladyland sessions and can be found on Cry Of Love. This album, another key part of our upbringing, was later released as First Rays of the New Rising Sun, a copy of which I have on CD and will be exploring later. But, back on Axis, after that crazy opening, the album surges into the first actual song, Up From The Skies, which Wikipedia calls a “jazzy number featuring Mitchell playing (drums) with brushes”. The song is about a space alien who has visited the earth thousands of years in the past, and returns to the present ‘to find the stars misplaced and the smell of a world that has burned”. Couched, of course, in inimitable Hendrix-mould rock, the song is a cry of pain for a blue planet that already then sensitive souls like Jimi knew was being wrecked. “I just want to talk to you. / I won’t uh, do you no harm, / I just want to know about your different lives, / On this here people farm.” Phew! I never heard that last line before. What a lovely sci-fi image – the Earth as a “people farm”. And I guess a visiting alien, where life may take on an altogether different form to ours, might easily have seen this as a farm full of people. The visitor seems incredulous that people live this way. “I heard some of you got your families, living in cages tall & cold, / And some just stay there and dust away, past the age of old. / Is this true? / Please let me talk to you.” What a lovely image for the tragic neglect of the elderly! He is persistent, armed as he is with a ray-gun-like lead guitar capable of unleashing unworldly sounds on unsuspecting humans. “I just wanna know about, the rooms behind your minds, / Do I see a vacuum there, or am I going blind? / Or is it just remains from vibrations and echoes long ago, / Things like ‘Love the World’ and ‘Let your fancy flow’, / Is this true? / Please let me talk to you. / Let me talk to you.” Then this visitor seems to experience an attack of déjà vu. “I have lived here before, the days of ice, / And of course this is why I’m so concerned, / And I come back to find the stars misplaced / And the smell of a world that has burned. / The smell of a world that has burned. / Well, maybe, maybe it’s just a change of climate. / I can dig it, I can dig it baby, I just want to see.” Those words, naturally, were prophetic. For certainly, as we look back over the past 40 years of careless industrial “progress”, we have to concede we have effected climate change and a world that in many areas is burning – literally and figuratively. And what a lovely way of describing having lived on earth before the last ice age – “the days of ice”. As the song unwinds, Hendrix slips into more flippant mode, somehow mocking the earthlings as they orchestrate their own demise. “So where do I purchase my ticket, / I would just like to have a ringside seat, / I want to know about the new Mother Earth, / I want to hear and see everything, / I want to hear and see everything, / I want to hear and see everything. / Aw, shucks, If my daddy could see me now.”

Track 3, Spanish Castle Magic, as mentioned earlier, referred to that dance hall in Des Moines where Hendrix jammed as a teenager. I remember a sprightly rhythm as this song transported one to another time, another place. “It’s very far away / It takes about a half a day to get there / If we travel by my uh, dragon-fly / No it’s not in Spain / But all the same you know, its a groovy name / And the winds just right. / Hey!” Riding on that old dragonfly, you are now borne aloft on the strains of Hendrix’s strings. “Hang on my darling / Hang on if you wanna go / Here it’s a really groovy place / It’s uh, just a little bit of uh, said uh, Spanish castle magic.” He is at his poetic best here. “The clouds are really low / And they overflow with cotton candy / And battle grounds red and brown / But its all in your mind / Don’t think your time on bad things / Just float your little mind around / Look out! ow!” Then, as that guitar and its accompanying wizardry of special effects engulf you, Hendrix pours out another chorus: “Hang on my darling, yeah / Hang on if you wanna go / Get on top, really let me groove baby with uh just a little bit of Spanish castle magic.” The improvised chirps and chatter continue, with things like, “It’s still all in your mind babe” and “Hang on my darling, hey / Hang on, hang on if you wanna go…” In all, another Hendrix classic, which I’d dearly love to hear again.

While Wikipedia may describe the next track, Wait Until Tomorrow, as a “pop song with an R&B guitar riff”, for us it was just more of the Hendrix magic, with Mitchell and Redding providing the backing vocals. Again, the lyrics bring the song back in an instant. Because, while the chorus is easy, a simple repeating of the line “We gonna wait till tomorrow”, I battled to recall how it started. Of course it is with a surge of electronic power, and the lines: “Well, I’m standing here, freezing, inside your golden garden / Uh got my ladder, leaned up against your wall / Tonight’s the night we planned to run away together / Come on Dolly Mae, there’s no time to stall / But now you’re telling me ...” And yes, it’s every loverboy’s nightmare. This gal ain’t going nowhere. Well not tonight anyways. Because she tells him, as a dialogue starts: “I think we better wait till tomorrow / Hey, yeah, hey / (I think we better wait till tomorrow) / Girl, what ’chu talkin’ ’bout ? / (I think we better wait till tomorrow) / Yeah, yeah, yeah / Got to make sure it’s right, so until tomorrow, goodnight. / Oh, what a drag.” Anyway, this guy is desperate to get his girl. “Oh, Dolly Mae, how can you hang me up this way? / Oh, on the phone you said you wanted to run off with me today / Now I’m standing here like some turned down serenading fool / Hearing strange words stutter from the mixed mind of you / And you keep tellin’ me that ah ...” And so the chorus is repeated, with the suitor interjecting that he can’t wait. “I think we better wait till tomorrow / What are you talkin’ ’bout ? / (I think we better wait till tomorrow) / No, can’t wait that long / (I think we better wait till tomorrow) / Oh, no / Got to make sure it’s right, until tomorrow, goodnight, oh.” That riff picks up again, before our protagonist tries another tack. “Let’s see if I can talk to this girl a little bit here...”, he says, before this final attempt: “Ow ! Dolly Mae, girl, you must be insane / So unsure of yourself leaning from your unsure window pane / Do I see a silhouette of somebody pointing something from a tree? / Click bang, what a hang, your daddy just shot poor me / And I hear you say, as I fade away ...” And of course all he hears, despite his gallant bid to win her hand in a Romeo and Juliet re-enactment, is her telling him they DON’T have to wait till tomorrow. How cruel is that for a guy with a bullet in his body. “We don’t have to wait till tomorrow / Hey ! / We don’t have to wait till tomorrow / What you say? / (We don’t have to wait till tomorrow) / It must have been right, so forever, goodnight, listen at ’cha.” The song ends with this dialogue between a guy who’s mortally wounded, and Dolly Mae who’s suddenly now ready to go with him. He at one point mournfully notes that “I won’t be around tomorrow, yeah!”, before adding “Goodbye, bye bye !” and “Oh, what a mix up / Oh, you gotta be crazy, hey, ow!”.

Do I recall the next track, Ain’t No Telling? Not at all, but I will when I check out the lyrics. Wikipedia says it is a rock song “with a complex structure for its short length (1:46 minutes)”. Ja, it comes back in an instant. Indeed, a complex little melody with surging, aggressive bass gets this one going. It is a song where I never really heard the words properly, instead focusing more on that intricate guitarwork. It goes like this. “Well, there ain’t no, / Ain’t no / Ain’t no telling, baby / When you will see me again, but I pray / It will be tomorrow.” These verses are short but sweet. “Well, the sunrise / Sunrise / Is burning my eyes, baby / I must leave now, but I really hope / To see you tomorrow.” Very well do I recall the line about putting “my body in her brain”, said with such vehemence, from the next verse. “Well my house is, oh, such a sad mile away, / The feeling there always hangs up my day / Oh, Cleopatra, She’s driving me insane, / She’s trying to put my body in her brain. / So just kiss me goodbye, just to ease the pain.” The song, in typical Hendrix style, winds down, and up, with the repeat of that chorus. Except that at the end he concludes that “Sorry, but I must leave now.”

And finally to a song, Little Wing, that I have on two compilations, one made for me by my late brother Alistair nearly 20 years ago – the only Hendrix track among stuff by Tom Rush, Melanie, Dave Bromberg and Bruce Cockburn. But it is also on a CD called The Ultimate Experience, so let’s at last get reacquainted with a snippet from this great album. How great to hear that opening guitar riff, accompanied by Mitchell’s tinkling glockenspiel, a subtle touch which gives the song just that added bit of class. Wikipedia says Little Wing is the “Indian name of Hendrix’s guardian angel”, adding that he himself said it was “his impression of the Monterey Pop Festival put into the form of a girl”. Whatever it is, it is one of his most beautiful compositions, which the Irish group the Corrs covered to good effect a few years ago. The lyrics are typically poetic. “Well she’s walking, through the clouds / With a circus mind that’s running wild / Butterflies and zebras / And moonbeams, and fairy tales / That’s all she ever thinks about / Riding with the wind.” Here Mitchell’s drums crackle like fireworks before the next verse begins. “When I’m sad she comes to me / With a thousand smiles she gives to me free / It’s all right she said, it’s all right / Take anything you want from me / Anything.” Then that final, liberating, message: “Fly on Little Wing / Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah / Little Wing.” Breathtakingly beautiful.

At 5:32 minutes, the final track on Side 1, If 6 Was 9, is the longest song on the album. Would that I had this one to hand. I remember it for its lovely imagery, while of course the numbers 6 and 9 also had rather rude sexual connotations which I hope I was not yet privy to at that tender age. Wikipedia says it is “arguably the most psychedelic track on the album”, and is notable for Gary Leeds of the Walker Brothers and Graham Nash “using their feet during the outro to make some stomping”. It notes further that the song features on the soundtrack for the 1969 counterculture film, Easy Rider, which I need to see at some point. This is probably also one of the few songs from the era I can recall which specifically mentions hippies and their hair. So there is this opening bit of psychedelic mayhem over which you hear the lines “(yeah, sing a song bro ...) / If the sun refused to shine / I don’t mind, I don’t mind / (yeah) / If the mountains ah, fell in the sea / Let it be, it ain’t me. / (well, all right).” Then the rejoinder: “Got my own world to live through and uh, ha ! / And I ain’t gonna copy you.” The next verse is in similar vein: “Yeah (sing the song brother ...) / Now if uh, six uh, huh, turned out to be nine / Oh I don’t mind, I don’t mind uh ( well all right... ) / If all the hippies cut off all their hair / Oh I don’t care, oh I don’t care. / Dig. / ’Cause Ive got my own world to live through and uh, huh / And I aint gonna copy you.” We loved that assertive stance taken by Hendrix, who was the ultimate individualist, carving an entirely new and exciting niche for himself. But the song takes on a different tone at this point. “White collar conservative flashin down the street / Pointin their plastic finger at me, ha! / They’re hopin’ soon my kind will drop and die but uh / I’m gonna wave my freak flag high, high ! / Oww ! / Wave on, wave on ...” There is of course a tragic irony in those lines. He lived just a few more years during which he did indeed wave his freak flag high, despite the opprobrium of the conservatives. And, while he may indeed have “dropped and died”, he continues to have the last laugh, because his music outlives the legacy of all his detractors. The winding down part of the song is a delight, filled with Hendrix’s unique sense not only of humour, but of the absurd. He failed to take anything too seriously, it would seem. “Ah, ha, ha / Fall mountains, just don’t fall on me / Go ahead mister business man, you can’t dress like me / Yeah !” At the time he was so confident of his path, so full of the power of life. “Don’t nobody know what I’m talkin about / I’ve got my own life to live / I’m the one that’s gonna die when its time for me to die / So let me live my life the way I want to.” I remember well how those lines were spoken in a kind of musical trance, like the words of a seer to his followers. Then, as the music magic pours out, he blesses their efforts: “Yeah, sing on brother, play on drummer.”

Da-daa da-da! Da-daa da-du. That’s how I recall the opening notes on You’ve Got Me Floating, the first track on Side 2 and eighth on the album. Wikipedia says it is “a rock song opening with a swirling backwards played guitar”, although this is only available on some mixes of the LP. “You got me floatin’ round and round, / Always up, you never let me down / The amazing thing, you turn me on naturally, / And I kiss you when I please.” I confess I never heard these intimate “nothings” between Hendrix and his girl, except subliminally. The chorus is a chanted “You got me floatin’ round and round, / You got me floatin’ never down / You got me floatin’ naturally / You got me floatin’ float to please.” Then, after a period of guitar-induced levitation, he’s back on the button. “You got me floatin’ across and through / You make me float right on up to you / There’s only one thing I need to really get me there, / Is to hear you laugh without a care.” The more than bearable lightness of being continues through a double dose of the chorus, before he returns for another bit of flattery. “Now your Daddy’s cool, and your Mamma’s no fool, / They both know I’m head over heels for you, / And when the day melts down into a sleepy red glow, / That’s when my desires start to show.” And isn’t that a wonderful image of a romantic sunset? In all, a delightful love song, but naturally one that is altogether unique.

And then, at last, another song I actually have on disc, Castles Made Of Sand, which Wikipedia calls “a ballad also making use of a backwards guitar solo”, whatever that means. Was it recorded and then played backwards, perhaps? Let’s see if a listen will reveal all. Phew again! This is another of those crisp, short masterpieces, which runs to 2:46 minutes. Hendrix on this and Little Wing is almost in folk-music mode, except he still is happier on an electric guitar. The strummed chords emerge out of silence before stalling to allow him to pluck out that complex introductory melody. Now, with drums and bass kicking in, the stage is set for some of Hendrix’s finest vocals in what really is, I suppose, a ballad, though the word seems far too conservative to be said in the same breath as Jimi Hendrix. This was one of the few Hendrix songs which included a narrative tale. But was I hearing it correctly all those years ago? “Down the street you can hear her scream you’re a disgrace / As she slams the door in his drunken face / And now he stands outside / And all the neighbors start to gossip and drool / He cries oh, girl you must be mad, / What happened to the sweet love you and me had? / Against the door he leans and starts a scene, / And his tears fall and burn the garden green.” Then, that guitar weaving a complex array of notes, he sings the short, cryptic chorus. “And so castles made of sand fall in the sea, eventually.” At last that clears up a misheard aspect for me. I thought he sang, “And sand castles made of sand”, which of course is terrible grammar. Here finally I stand corrected. I loved the next verse, which no doubt references Jimi’s Indian (Native American) roots. “A little Indian brave who before he was ten, / Played war games in the woods with his Indian friends / And he built a dream that when he grew up / He would be a fearless warrior Indian Chief / Many moons past and more the dream grew strong until / Tomorrow he would sing his first war song and fight his first battle / But something went wrong, surprise attack killed him in his sleep that night.” So thus far we have two tales of lives that are either destroyed by lost love, or at a time when the child is on the brink of becoming a man. Castles, as we made them on the beach, are so easily flattened by the surging sea. Then came the poignant tale of a young girl in a wheelchair. “There was a young girl, who’s heart was a frown / ’cause she was crippled for life, / And she couldn’t speak a sound / And she wished and prayed she could stop living, / So she decided to die / She drew her wheelchair to the edge of the shore / And to her legs she smiled you wont hurt me no more / But then a sight she’d never seen made her jump and say / Look a golden winged ship is passing my way / And it really didn't have to stop, it just kept on going...” With this sense of salvation by a visiting space ship, that “backward” guitar really seems to get excited and wail and cry its muted notes into the bowl of sound created by some superb bass, drums and rhythm guitar. Heaven knows how that sound is achieved, but it is what gives this song such superb texture. Even though the last line of the song, as it winds down, suffers from errors of concord, poetic licence is indeed readily granted. “And so castles made of sand slips into the sea, eventually.” A wailing guitar fades into the distance…

And of course Hendrix was playing alongside highly skilled musicians, in the Cream mould. So it is no surprise to find him playing second fiddle, as it were, to Noel Redding, who does the lead vocals on his composition, She’s So Fine, which Wikipedia calls a “very British pop/rock/Who influenced affair”. I remember it as a very subtle, understated piece of psychedelia. “She walks with a bell-clock round her neck, / So the hippies think she’s in with time / Her hair glistens like robins on a deck / Branches attack me from her neck.” After those wonderful lines, the chorus. “She’s so fine / She’s so very, very fine.” I suppose this is all just a bit of whimsy, but it certainly sounds good as a song, given that Hendrix adds his unique touch. “The sun from a cloud sinks into her eyes / The rain from a tree soaks into her mind, mind … / Morning sign sounds just like a lock / all the sings are always a stock.” Not sure what that’s about. Then that chorus before: “When I veer I get so near / But so far far far away / Listen to me today. / We united just beside a leaf / The ground was hard underneath, her, her / She’s so fine.” Thank heavens Hendrix was around to write most of the stuff, because this lacks his finesse.

Rainy day, dream away… That was still to come, on Electric Ladyland. But what was One Rainy Wish about? The 11th track on Axis, Wikipedia says it “begins as a ballad but develops a rock feel during the chorus that is in a different time signature to the verses”. From the title, and in the absence of the song in any form, I cannot say I recall it offhand. However, the lyrics will no doubt spur instant recognition. Ah, the ravages of time! Even though the lyrics look mighty familiar, the song remains just out of memory. It is nonetheless a fine piece of Hendrix poetry, which one day I’ll rediscover in its intended format. “Golden rose, the color of the dream I had / Not too long ago / A misty blue and the lilac too / A never to grow old.” There’s a lovely surreal quality to this. “A there you were under the tree of song / Sleeping so peacefully / In your hand a flower played / A waiting there for me.” My heart tells me this is one of those all-time classic understated Hendrix masterpieces. “I have never / Laid eyes on you / Not like a before / This timeless day / A but you walked and ya ha / Once smiled my name / And you stole / My heart away / A stole my heart away little girl, yeah / All right!” After the chorus is repeated several times – no doubt to rousing guitar-led musical accompaniment – the change spoken of seems to occur. “It’s only a dream / I’d love to tell somebody about this dream / The sky was filled with a thousand stars / While the sun kissed the mountains blue / And eleven moons played across rainbows / Above me and you. / Gold and rose the colour of the velvet walls surround us.” I certainly do recall that line “the sun kissed the mountains blue”, which might even have been spoken. And how’s the image, “eleven moons played across rainbows”. Superb! Even without the music, man.

The penultimate track, following what was clearly a gentle song, had to be a fully fledged rocker, and that is how I remember Little Miss Lover. Wikipedia says it was the first song “to feature a percussive muted wah-wah effect (with the fretboard hand ‘killing’ notes) – a technique that was later adopted by many guitarists”. This time I know the lyrics will jolt the song to memory’s life. While the song runs for 2:20 minutes, it is essentially an instrumental. “Little Miss Lover / Where have you been in this world for so long?” This is followed by: “Excuse me while I see if that gypsy in me is right / If you don’t mind. / Well, he signals me okay / So I think it’s safe to say / I’m gonna make a play.” Oh how I’d dig to hear that again. Happily I’ll be able to do so with the last track, which is on one of those compilations.