STEVE Winwood, who was born in

I recently picked up a copy of an early Traffic album at my favourite second-hand vinyl shop. In fairly good nick, it is just titled Traffic, and features that incredibly evocative song, Forty Thousand Headmen, which is also on Welcome to the Canteen.

Having just given it a fresh listen, I was struck by the crisply played lead guitar on innovative blues-rock songs. But more about that later.

Jim Capaldi and Dave Mason are the two other names of Traffic band members which stand out, particularly as they were almost as prodigious song-writers as Winwood. But it was Winwood’s vocals, and several key acoustic-guitar-based songs which really put Traffic up their with some of the world’s best in the early 1970s, my high school years, when I seemed to ingest more music than I probably ever had time for. But I suppose there are sixty minutes in an hour and 24 hours in a day – and you can fit a helluva lot of music into even 12 hours. When you were as obsessed with music as we were, it is therefore not surprising we imbibed these sounds gluttonously.

Perusing my first Wikipedia download – sans pictures since it requires less space to store the info that way – I was immediately reminded of my key omission in the introductory remarks above. Chris Wood. For was it not he that injected the flutes and saxophones into the Traffic sound which was such a vital part of the overall package?

Classified as purveyors of psychedelic and progressive rock, the band was active from 1967 till 1974, arguably the pivotal years for music in the “revolution” I’m attempting to discuss.

One of the least “hip” parts of

Steve Winwood

So how did it all happen, and why the name Traffic?

Well nothing is easy in the world of rock group formation. Wikipedia tells us Steve Winwood became friends with his future band mates “in the latter days of the Spencer Davis Group”. And that is another blast from the past.

With Winwood, Capaldi, Wood and Mason having often jammed together at The Elbow Room club in Aston,

The group’s debut album was Mr Fantasy which, says Wikipedia, was a hit in the

And I don’t think I’m going to discover how they got their name, though, considering their last live album, from 2005, is called “Last Great Traffic Jam”, it is possible this pun had been the origin since those early days of the four jamming together.

The Beatles had done it, now it was Traffic’s turn. How to break into the lucrative

And now comes the biggie. Because after the end of the Blind Faith experiment, in 1969, says Wikipedia, Winwood started work on a solo recording “which eventually turned into another Traffic album (without Mason)”. The resultant John Barleycorn Must Die was “their most successful album yet”. Then, possibly a mistake after the success of John Barleycorn, they expanded the group in 1971, adding Ric Grech on Bass, Jim Gordon of Derek and the Dominoes (Clapton’s band) on drums, and percussionist Rebop Kwaku Baah. They released Welcome to the Canteen in September 1971. I’ll discuss these great albums a little later, but it is interesting to recall that that classic black and white cover photograph of the six guys sitting in a restaurant does not in fact have the name Traffic on the cover. Instead, it simply lists their names, with the title at the base of the sleeve. And, believe it or not, Dave Mason was back in favour, making his third and final spell with the band. Two songs from his recent solo album, Alone Together, were included, along with a cover of the Spencer Davis Group song, Gimme Some Lovin’.

Before getting on to the latter years of the Traffic era, it is probably fitting to look at those first albums in more detail.

Mr Fantasy

Mr Fantasy, Traffic’s debut album from December 1967, was released after Dave Mason had already left the band. And correction, there is no title track. Dear Mr Fantasy is the title of the song, and subsequent single, on the album. I did not experience this album, which Wikipedia says was “considered by far the strangest and most ‘art rock’ style album that Traffic released”. It features “more horns, flutes, and less rock-style instruments than most of Traffic’s future releases”. Under Mason’s influence, the sitar was also used “much more on this album than any other later Traffic albums”. What is notable, looking at the track listing, is that all the Mason songs are solo compositions, whereas the other three all collaborated on their songs, though Mason was part of Giving To You, which involved all members.

Traffic

The eponymously titled Traffic album, released in October 1968, is classified by Wikipedia as jazz rock and art rock, as well as psychedelic rock and acid jazz. Yet, says Wikipeida, after that debut album, Mr Fantasy, Traffic “planned a more mainstream album, possibly with fewer drug references and psychedelic influences”. Having reinstated Mason, he proceeded to write and sing about half the album, “making almost no contribution to the other half”. Interestingly, having just listened to the album, I had the same thought as Wikipedia mentions when it says that Chris Wood’s flute playing on the album “was compared to that of Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull”.

The long auburn-tinged brown hair of Steve Winwood contrasts with his velvety green shirt. Wearing orange jeans, he occupies “centre stage” on the cover, which also features Chris Wood pointing. This draws attention to the “Traffic symbol”, four U-turn type arrows which together make a rounded square. Wikipedia says every Traffic album features the symbol somewhere on the front and/or back cover.

I’m not sure if the

The Winwood/Capaldi song Pearly Queen soothes one initially with gentle acoustic guitar and organ, before the sudden advent of heavy drums with attendant vocals: “I bought a sequined suit from a pearly queen / And she could drink more wine than I’d ever seen / She had some gypsies’ blood flowing through her feet / And when the time was right she said that I would meet / My destiny.” My destiny. This is Winwood’s vocals, and they are out of this world. When he sings those words, you know you’ve arrived at the true Traffic sound. “I travelled round the world to find the sun / I couldn’t stop myself from having fun / And then one day I met an Indian girl / And she made me forget this troubled world / We’re living in.” The lead guitar on this track is Claptonesque, while the drumming too is superb. The arrangement is inventive, with regular changes of tempo. At one point, the lead guitar recalls that on the Stones’ Paint It Black. There is even some incredible blues harmonica. The song concludes with the lines: “I had a strange dream. In my hair / I saw a pearly queen lying there / And all around her feet flowers bloomed / But they were made of silk and sequins two by two.”

Mason’s Don’t Be Sad is a slow rock, his alto vocals recalling the later Fleetwood Mac songs. This song features strong vocal harmonies, great lead guitar and some more inventive drumming. The organ is often pitched to sound like a female backing group. “Don’t be sad, I just want to see you get through / All I have, it’s yours if you think it helps you / Good or bad, there’s no one can really judge you / You just have to come to your own conclusion / There is only one who means more than all to me / And through the lady, in a dream I’ve learned to live with everyone / Mother, father, all my friends, have seen me have my day / But now I see that there’s no need in trying to run, though it’s been fun.” Not necessarily brilliant lyrics, but another great vehicle for the flow of Traffic.

Where were they headed? Who Knows What Tomorrow May Bring. That was the title of the next track, another Winwood/Capaldi collaboration. Winwood’s strong blues vocals are again a hallmark of this slow, bluesy track where the lead guitar and organ are again superb. The lyrics are short, but sweet. “We are not like all the rest, you can see us any day of the week / Come around, sit down, take a sniff, fall asleep / Baby, you don’t have to speak / I’d like to show you where it is but then it wouldn’t even mean a thing / Nothing is easy, baby, just please me, who knows what tomorrow may bring? / If for just one moment you could step outside your mind / And float across the ceiling, I don’t think the folks would mind.” It was all about shocking the oldies, I think.

For a while, Winwood aside, it was a Mason track that defined the Traffic sound. And the last track on Side 1, Feeling Alright?, was that sound. With a pleasant acoustic guitar foundation, the song features tight bass and drums, and strong piano work, while a sax break near the end prefigures the wonders that Chris Wood would achieve on John Barleycorn. Fittingly, Mason’s bass is dominant throughout this song, which contains lines no Traffic lover will be unfamiliar with. “Seems I’ve got to have a change of scene / ’Cause every night I have the strangest dreams / Imprisoned by the way it could have been / Left here on my own or so it seems / I’ve got to leave before I start to scream / But someone’s locked the door and took the key.” Then that famous chorus: “You feelin’ alright? I’m not feelin' too good myself / Well, you feelin’ alright? I’m not feelin’ too good myself.” I think it’s something most drug-taking youths asked each other from time to time. It became quite a thing. In what should have been the flush of healthy youth, you are suddenly concerned that you might be losing it – because you happened to have smoked all that stuff on top of drinking that booze and popping those pills. “Not feelin’ too good myself, man.” But what the heck, let’s have another joint… Of course for most of us, it was about what to do with all that time, which, had you been lucky enough to be scoring with a beautiful chick, you would not have needed to spend doing antisocial things. Because this song is about a relationship. “Well, say, you sure took me for one big ride / And even now I sit and wonder why / That when I think of you I start to cry /I just can’t waste my time, I must keep dry /Gotta stop believin’ in all you lies / ’Cause there’s too much to do before I die.” Yeah. Ja. Yes. It was like that. A matter of life and death. Some okes, ous, guys, went mal, mad, gaga, from the drugs. I remember encountering one of our “gang” about five years after those heady high school days, and he was stuffed, virtually a vegetable. So Mason concludes with: “Don’t get too lost in all I say / Though at the time I really felt that way / But that was then, now it’s today; / I can’t get off so I’m here to stay / Till someone comes along and takes my place / With a different name and, yes, a different face.”

Now, as if that hormonal angst isn’t bad enough, Side 2 starts with something called Vagabond Virgin, by Mason and Capaldi. Like the first track on Side 1, this is a light, whimsical piece, which again features great acoustic guitar and piano. And, as the bass again leads the play, one gets the first sighting, or sounding, of that beautiful flute. But what was Mason on about this time? Before I check out the lyrics, it is interesting to note, in these days of crass commercialism – without which the lyrics wouldn’t be pasted all over the Net – that each set of lyrics includes an advert for ringtones. Who would want a Traffic ringtone on their cellphone – apart from people my age, that is, and frankly most of us couldn’t care what that ringtone sounds like. Anyway, Vagabond Virgin, which has nothing to do with Richard Branson, goes like this: “Tell me how you want me to be, then look again and you will see / That I’m still the same love / Think me into any shape, your twisted mind has no escape / But don’t be ashamed, love, it’s just a game, love / But don’t be ashamed, love, it’s just a game, love / You can learn how to play / Born like you were in a terrible mess, didn’t know what it was to have a new dress / You just wanted to scream out my name / Till somebody said, ‘Let me take you to bed’ / And with money and lies they filled up your head / You were barely thirteen, a child from the villages / So fresh on the scene.” This song, with its strong folk undertones, certainly anticipates John Barleycorn, and Chris Wood’s flute, alongside the acoustic guitar, sounds sublime. Mason’s vocals, ably backed by the others, is another high point of the early Traffic sound, irrespective of the difficult dynamic between him and Winwood.

But if we’re looking for the definitive Traffic sound, the next track, Forty Thousand Headmen (Winwood/Capaldi) must be right up there with the best. Indeed, that flute/acoustic guitar collaboration reaches a

Not to be outdone, Mason returns the fire on the next track, Crying’ To Be Heard, which emerges from a slow blues, with baritone sax and organ, which lulls you into a false sense of peace and quiet. Suddenly, the words are torn out, bursting the bubble: “Somebody’s crying to be heard / And there’s also someone who hears every word…” The song slows for the first verse, acoustic guitar prominent: “Sail across the ocean with your back against the wind / Listening to nothing save the calling of a bird / And when the rain begins to fall, don’t you start to curse / It may be just the tears of someone that you never heard.” I thought I detected a harpsichord somewhere here, while later on the organ is reminiscent of Strawbs’s Rick Wakeman at his finest. Indeed, the song builds to a considerable crescendo, with lead guitar, sax, organ and drums, not to mention the Masonic bass, jamming together and indeed being heard.

To use that awful verb, this track again seques into No Time To Live, a Winwood/Capalidi track, with organ and piano emerging quietly. The insistent piano builds until some Phantom-of-the-Opera-type chords ring out. This time it is the saxophone that delivers the wind section, before Winwood’s voice takes centre stage: “As time begins to burn itself upon me / And the days are growing very short / People try their hardest to reject me / But in a way, their conscience won’t be caught.” Look, these aren’t necessarily the greatest lyrics, but if ever the Winwood voice was to be tested it was here. I was reminded of Ian Gillan, in the role of Jesus on Jesus Christ Superstar at times, his voice often soaring alongside that immaculate high-pitched sax. These verses sound far more impressive within the context of this dramatic song, with Winwood giving each word his all: “Something’s happening to me day by day / My pebble on the beach is getting washed away / I’ve given everything that was mine to give / And now I’ll turn around and find that there’s no time to live.” The final verse: “So often I have seen that big wheel of fortune / Spinning for the man who holds the ace / There’s many who would change their places for him / But none of them have ever seen his lonely face.”

The album concludes with another Winwood/Capaldi song, Means To An End, a quicker blues-rock. Indeed, two lead guitars near the end get positively raucous. “Well, you told me you were sorry, when I needed your advice / And I was too confused to see the meaning / Like Peter, you disowned me with a voice as cold as ice / And before the fire died and they were leaving.” With the reference to Peter, this really does recall JC Superstar. But it is during this chorus that the electric guitar really soars and scythes between Winwood’s powerful vocals: “I’m a means to an end and everybody’s friend / To a richman, poorman, beggar man or thief / From my heart I send a messenger to bend / And take your mind from agony and grief.” Listening to this again, it is not surprising the words were lost, as Winwood’s vocals and those guitars do tend to compete for space. The last verse, rarely heard, runs: “Oh, sweet silence without kings and queens / No one here has ever reached your centre / Better to be quiet than to speak without a thought / Or you may lose the meaning of your venture.” A trifle forced, I would suggest.

Nevertheless, this is a fine, fine album, setting the band up for the masterpiece called John Barleycorn.

Last Exit

But before that was Last Exit which, though it was doing the rounds at the time, I don’t recall us ever having. And it seems, judging from Wikipedia, it was not to be taken too seriously. Traffic’s third album was “a collection of odds and ends put together by Island Records after the initial breakup of the band”, says Wikipeida. While photos of all four band members appear on the cover, “Mason does not actually appear on most of the album”. One of the stand-out titles on this album is Medicated Goo, which we would encounter later on Welcome To The Canteen.

John Barleycorn Must Die

And so to John Barleycorn Must Die. Incredibly, for such a pivotal album, when I downloaded information off Wikipedia they had very little on this work. Wikipedia notes that the album, from 1970, features “different genres of music including art rock, jazz rock, and many psychedelic influences”. My personal view is that the title track is obviously a traditional English folk song, adapted to the folk rock era, but still relying on some superb acoustic guitar work, supplemented by flutes and sax. As noted earlier, it was initially going to be a Winwood solo album, but with Chris Wood and Jim Capaldi joining in, it became Traffic once more. It was the first Traffic album to achieve gold record status. In the tradition of Blind Faith and Cream, the album has just six tracks, ranging from 4:02 minutes to 7:05, which gives the band ample opportunity to include those brilliant passages of innovation for which it is rightly renowned. Significantly, and this I’ve gleaned off the cover of the original vinyl album, there seem to be no electric guitars on the entire set. And this may be the key to its success, offering a softer form of progressive rock built around organ and wind instruments, with a solid electric rhythm section.

Reminiscent, in a way, of that great Neil Young cover for Harvest, in this case the album uses black and white woodcuts from the English Folk Dance & Song Society, with a bushel (would it be?) of barleycorn on the front, and another of a scarecrow on the back. Inside, the album features one of the coolest picture in the history of rock, with Winwood, Capaldi and Wood shown in colour in their hippest gear against a cloud-strewn, greenish sky. All the tracks are credited to Winwood-Capaldi, apart from Glad (Winwood alone) and the title track, which I see is actually just called John Barleycorn (without the “must die”), which is a traditional song arranged by Winwood.

After listening to the album, I have to say it is every bit as good as I remembered it, conceding however that there is no way that one will ever be able to capture within one the sort of mood, or sentiment, one experienced as a teenager hearing this stuff when it was new and fresh out the box, as it were. Yet, having the perspective of nearly four decades does help one appreciate other factors overlooked at the time. The first is that this is probably Steve Winwood’s masterpiece. Certainly the album is credited to Traffic, but it is Winwood who provides the bulk of the work, and it is beautiful stuff! And what a brave move to open with an instrumental track, Glad, which is arguably the best on the album. I was reminded of John Mayall’s The Turning Point album by the interesting array of sounds on this bluesy, jazzy piece, with some extravagant piano and organ flourishes by Winwood augmented by incredible Chris Wood sax. And how do they get by without an electric guitar? Why, by Wood also using an electric sax, which provides a wah-wah effect that could in fact easily be mistaken for a guitar. Only, because it’s a sax it is just that much more interesting.

Naturally, the song doesn’t just end, it flows seamlessly into a tight bit of piano and sax which, with a sharp rap on the drums, heralds the first vocals on the album, in Windwood’s inimitable voice: “Like a hurricane around your heart when / earth and sky are torn apart / He comes gathering up the bits while / hoping that the puzzle fits / He leaves you, he leaves you. / Freedom rider.” I’d never read those lyrics before, despite “knowing” this song intimately for so long. It is on this track that Wood unleashes the flute to its full potential, at times rivalling, perhaps even surpassing, the sound of Ian Anderson. I assume Winwood also plays bass on here, as no one else is listed as doing so, because it too is brilliant. “With a silver star between his eyes / that open up at hidden lies / Big man crying with defeat, sees people gathering in the street / You feel him, you feel him. / Freedom rider.” These lyrics look as impressive as they sound, giving the song a sense of class and quality which would have been lost had the lyrics been weak and half-baked, the downfall of so many rock, especially hard rock, songs. “When lightning strikes you to the bone, / you turn around, you're all alone / By the time you hear that silent (siren?) sound, then your soul is in the / lost and found / Forever, forever. / Freedom rider / Here it comes.”

Empty Pages, also a Winwood-Capaldi collaboration, is another of those slow blues numbers which rely on some superb piano playing by Winwood, with Wood this time contributing the organ, and Capaldi again on drums and percussion. It is the interaction between the piano and drums which is such a key component here, as the song begins incisively, before mellowing: “Found someone who can comfort me, but there are always exceptions / And she’s good at appearing sane, but I just want you to know / She’s the one makes me feel so good when everything is against me / Picks me up when I’m feeling down, so I’ve got something to show.” Then that chorus, which I again read for the first time. Remember that it is accompanied by feisty music and drumming: “Staring at empty pages, centred ’round the same plot / Staring at empty pages, flowing along in the ages.” As I noted earlier, we, I never really cared too much what was being sung. It was the mood that mattered, with Winwood’s voice providing it. But the words were always there to be explored and understood, and even those bits which were readily heard added to the ambience. “Often lost and forgotten, the vagueness and the mud / I’ve been thinking I’m working too hard, but I’ve got something to show.” The song then returns to that lovely chorus, with its crashing drums and cymbals, before slowing to enable Winwood to manufacture an intricate piano solo against the foil of his own voice.

An integral, vital, part of this album’s character is the use of an acoustic guitar on the opening track on Side 2, Stranger To Himself. Working in tandem with the piano, the steel-strung guitar gives the song a lovely edge, while Capaldi provides more than adequate vocal harmonies. Again, the song provides a platform for some more incredible rock improvisations, with Winwood introducing the electric lead guitar for the first time on the album (so there was one!). The lyrics seemed to talk to our troubled teenage souls: “Struggling with confusion, disillusionment too / Can turn a man into a shadow, crying out from pain.” Did I really take not of these words at the time? No, I only heard about half of them, and never cared about their meaning, to tell the truth. Yet, had they been weak, I would have known immediately, and the song would have been ruined. You had to know you were listening to guys with brains, not some illiterate, inarticulate half-wits. “Through his nightmare vision, he sees nothing, only well / Blind with the beggar’s mind, he’s but a stranger / He’s but a stranger to himself.” I never imagined that was what was being sung, but I like it.” I was sucked into the rhythm, the blues, of this song, and loved the way its tension seemed to be echoed in the lyrics, so ably sung, but I wasn’t registering what was being sung: “Suspended from a rope inside a bucket down a hole / His hands are torn and bloodied from the scratching at his soul.” I heard all those words – bucket down a hole, and torn and bloodied – but never put the full sentences together. Which is probably just as well. No need to brood on the issues that drove these geniuses, rather simply enjoy the product in your own way. Yet it is great to finally see what it was they were saying, safe in the realisation that nearly 40 years on I am inured, I hope, to the angst these lyrics may engender.

It was always track 2 on side 2 that I wanted to hear most, despite lapping up the heavier electric music on this album. I was a sucker for traditional English music, and Irish, obviously, and John Barleycorn was sung most beautifully by Steve Winwood, who also plays some of the finest acoustic guitar one is likely to hear on a rock album. From intricate finger-picking, to full-blooded strumming as the song increases in intensity, he is a master of this instrument. Capaldi’s support vocals are perfectly pitched to complement Winwood’s totally distinctive work on this song. The album cover notes reveal that there are between 100 and 140 versions of this song in

The album ends, fittingly, on a high note, with one of the band’s all-time classics, Every Mother’s Son, another Winwood-Capaldi composition. Piano, organ, lead guitar launch this slow bluesy work, with Capaldi’s drumming as sympathetic as ever towards that unique Winwood voice. But once again, apart from a few key words, the lyrics were never fully formed in my psyche, so let’s get a feel for them now: “Once again I’m northward bound, on the edge of sea and sky / Tomorrow is my friend, my one and only friend / We travel on together searching for the end / I’m a travelling soul and every mother’s son / Although I’m getting tired I’ve got to travel on / Can you please help, my god? / Can you please help, my god? / Can you please help, my god? / I think it’s only fair.” All that just builds relentlessly, in a flash of brilliance. It sets the tone for the entire song, which includes lashings of inspired improvisation on organ and lead guitar before winding down for the final stanza: “Once again I’m northward bound, on the edge of sea and sky / Together we will go and see what waits for us / A backdoor to the universe that opens doors…” That long chorus again kicks in again, ensuring the song never loses its spark. I salute this album as one of the great achievements in rock history. No more, no less.

Welcome to the Canteen

As noted earlier, Welcome to the Canteen (September, 1971) did not carry the name Traffic on its front cover. Instead, just the names of the seven artists are recorded at the top of the black-and-white photograph of them sitting in, well, a canteen, or restaurant, of the sort in the

Medicated Goo, a Winwood/Miller composition, became another of those instantly recognisable Traffic hits. It was originally on their album, Last Exit, and as with most of the tracks here, the vocals are somewhat overwhelmed by the band on this jazzy, bluesy rock number. This is hard rock at its best, with all the elements – bass, lead guitar, drums, vocals, piano – working well together. Again, thanks to the muffled nature of the vocals, which none-the-less reveal Winwood at his expressive best, the precise lyrics were largely lost on me, so here’s a look: “Pretty Polly Possum what’s wrong with you? / Your body’s kind a weak / and you think there’s nothing we can do / Good Golly Polly shame on you / Cause Molly made a stew that’ll make a newer girl out of you.” One can hear the tune in those lyrics, with words just rolling out at pace, before the more familiar chorus: “So follow me, its good for you / That good old fashioned Medicated Goo / Ooo, ain’t it good for you? / My own homegrown recipe’ll see you thru.” I hadn’t realised this was a fun alliterative exercise: “Freaky Freddy Frolic had some, I know / He was last seem picking green flowers in a field of snow / Get ready Freddy, they’re sure to grow / Mother nature just blew it / and there’s nothing really to it I know.” Kinda makes you wonder what this “medicated goo” might be, reading that last verse. “Aunty Franny Prickett and Uncle Lou / They made some Goo / Now they really sock it to their friends / Frantic friends and neighbours charge the door / They caught a little whiff / Now they’re digging it and seeking more.” How naïve I’ve been, not spotting earlier that this was advertising some kind of “upper” that was all the rage at the time.

One normally associates Winwood with the wooden sound on Traffic albums, with the acoustic guitars and folk-type ballads. But on Sad And Deep As You, the second track, it is Dave Mason who sucks it to us in a classic live performance characterised by immaculate finger-picked acoustic guitar. Indeed, I notice on the Wikipedia notes about this album that Mason is responsible for all the acoustic guitar work on the album, which sort of explodes my earlier assumptions. A feature of this album is the growing prominence given to various percussion instruments, including conga and bongo drums. Rebop Kwaku Baah is the man responsible for this sound, and he certainly brings an interesting “world music” dimension. It is much to the fore on this track. So, too, the flute of Chris Wood, which is, in a sense, the spiritual heart of the song. Mason doesn’t have Winwood’s beautiful voice, but his is distinctive and characterful, and it more than succeeds on this song. And what better subject for testosterone-charged youths to get their teeth into? “Lips that are as warm could be / Lips that speak too soon / Lips that tell a story / Sad and deep as you.” Is it a story of love, and loss? “Smile that’s warm as summer sun / Smile that gets you through / Sad and deep you / Eyes that are the windows / Eyes that are the dew / Eyes that tell a story / Sad and deep as you / Tears that are unspoken words / Tears that are the truth / Tears that tell a story / Sad and deep as you.” Again, as with most great poetry, the final interpretation is left with the listener/reader. It is, however, an inspired piece of writing, simple but ever so effective. And the applause it receives from a previously gobsmacked audience speaks volumes.

So it is Dave Mason, then, who plays that beautiful acoustic guitar accompaniment to Winwood’s voice on Forty Thousand Headmen. As observed earlier, this is one of the great Traffic tracks, and even though Winwood’s voice is somewhat lost at times probably due to poor mixing, this gives the song added mystery. Because this was the only version I knew – until I picked up that old vinyl copy of Traffic, the second album, a few years ago. Flute, congas, bongos and some evocative acoustic guitar work see this song evolve into one mega laid-back Traffic jam towards the end.

Anyone familiar with Traffic will recognise the opening notes, on organ, of the next track – daa-da-daa-da, daa-da-daa-da. Another Mason song, Shouldn’t Have Took More Than You Gave is a great slow, bluesy rock number where Winwood’s lead guitar (or is it Mason?), including the extensive use of the wah-wah pedal, is a stand-out feature on some lengthy improvisations. The bongos again add interesting tonal textures, with the song returning every so often to that opening signature. But what was it that he took? I’m sure Mason will be gallantly vague in that regard. Well I was wrong again. It seem SHE did the taking. “You shouldn’t have took more than you gave / We wouldn’t be in this mess today / And though we’ve gone our separate ways / The dues we have to pay are / still the same.”

Winwood’s vocals really make Dear Mr Fantasy, from that earlier album. A Capaldi/Winwood/Wood composition, this slow blues again features strong lead guitar and organ, as it gradually mutates into a full-blooded rock sound, the lengthy improvisations reminiscent in a way of the great CSNY jams. With two lead guitars competing, the song’s denouement is an interesting and extended process. Fantasy seemed to be a favourite word in the Traffic dictionary. They’d even have a factory for it, later on. But here it is about music: “Dear Mister Fantasy play us a tune / Something to make us all happy / Do anything take us out of this gloom / Sing a song, play guitar / Make it snappy / You are the one who can make us all laugh / But doing that you break out in tears / Please don’t be sad if it was a straight mind you had / We wouldn’t have known you all these years.” Again, nothing too clear and straight-forward there.

Gimme Some Lovin’, the last track on the album, was written by the Winwood brothers and Spencer Davis back in the days of the Spencer Davis Group. It is a mot interesting track, starting with drums and bongos, even a bit of handclapping and some understated lead guitar. A simple melody comprising a few notes – almost simply a rhythm really – ensures a sparse, almost repetitious song which has a rough saw-dusty texture. While some would argue it is too long and unchanging, there are some inspired flashes of saxophone and the bongo-conga sound keeps the interest up. Again, the lyrics are muted. But again, too, the lines of verse have a rhythm all their own, and they ensure the song surges ahead: “Well, my temp’rature’s risin’ and my feet on the floor, / Twenty people knockin’ ’cause they’re wanting some more, / Let me in, baby, I don’t know what you’ve got, / But you’d better take it easy, this place is hot / So glad we made it, so glad we made it / You gotta gimme some lovin’, gimme some lovin’ / Gimme some lovin’ every day.” It was a remarkable album which remains one of the icons of this era.

The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys

It was now that my interest in Traffic waned a trifle. With Mason again leaving, they released The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys (November, 1971), which was a hit in the

The title track was a bit of a favourite at the time, with most of us happily singing along during the choruses. But I hadn’t realised till now that it ran to 11: 35 minutes, and contains numerous and diverse jams and improvisations. The song has a strong, jazzy introduction, featuring acoustic guitar, sax and bongos, with some stunning bass lines. An organ and a piano add to the colour. “If you see something that looks like a star / And it’s shooting up out of the ground / And your head is spinning from a loud guitar / And you just can’t escape from the sound / Don’t worry too much, it’ll happen to you / We were children once, playing with toys” It is about here that the urgency increases: “And the thing that you’re hearing is only the sound / Of the low spark of high-heeled boys.” Lead guitar and sax solos, along with inventive piano riffs, permeate this jazz rock odyssey. “The percentage you’re paying is too high-priced / While you’re living beyond all your means / And the man in the suit has just bought a new car / From the profit he’s made on your dreams / But today you just read that the man was shot dead / By a gun that didn’t make any noise / But it wasn’t the bullet that laid him to rest / Was the low spark of high-heeled boys.” So there is violence afoot here, too, if you’ll pardon the pun. “If you had just a minute to breathe / And they granted you one final wish / Would you ask for something like another chance / Or something similar as this / Don’t worry too much, it’ll happen to you / As sure as your sorrows or joys.” There is some ugly syntax in there, but let’s see where we end up: “If I gave you everything that I owned / And asked for nothing in return / Would you do the same for me as I would for you or take me for a ride / And strip me of everything, including my pride / But spirit is something that no one destroys ...” Then that final refrain: “And the sound that I'm hearing is only the sound / Of the low spark of high-heeled boys / Heeled boys.”

Jim Capaldi makes his, I believe, solo vocal debut on his own composition, Light Up Or Leave Me Alone. Again, not too familiar to me, this hard rock song has an almost Beatles quality, with some great lead breaks.

But Winwood is back at his sublime best on the next song, Many A Mile To Freedom, a 7:26 minute opus co-written with Anna Capaldi. A gentle rock song, with overarching flute, there are some strong, The Who-like bass notes and chords. The lyrics also flows beautifully, the song capturing something of the quality of the great early Traffic songs.

Bassist Ric Grech, who also plays violin somewhere on the album, though I couldn’t find where, co-wrote Rock & Roll Stew with Jim Gordon. “Sometimes I feel like I’m fading away …” Here Capaldi’s vocals are stronger, giving a performance of a great bluesman. There is an interesting passage where the wah-wah guitar and organ interact, under an overlay of organ, and electric piano.

The album ends with another epic, Rainmaker, which runs to 7:39 minutes and hangs on a pleasant melody built around the repetition of the word, rainmaker. Soothing acoustic guitar and flutes give this a gentle folk-rock feel. A creative sax solo near the end helps transforms the song into a slow bluesy jam.

Despite the long tracks, and jams, this album peaked at No 7 on the US’s Billboard Pop Albums chart in 1972. It may not have the heft of the earlier albums, but still finds the lads close to the peak of their abilities.

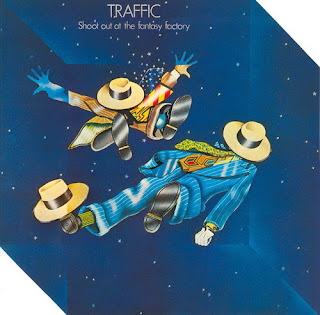

Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory

It was after this album that Capaldi started working on a solo career though he remained with the band. But Grech and Gordon left. However, they were latecomers anyway, so with Capaldi, Winwood, Wood and Rebop still there, Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory (released in January 1973, but recorded in December, 1971) was completed using drummer Roger Hawkins and David Hood on bass. And, not surprisingly, it was “another hit”, says Wikipedia, reaching No 6 in the

Oh How We Danced

For a while, Capaldi was the man to watch. I recall once borrowing my classmate Jeremy’s copy of Oh How We Danced (1972), only to foolishly leave it lying on the back seat of the car, in the sun. It ended up a warped and twisted version of the original. Can’t recall how I made it up to Jerry. A few years back I found a vinyl copy of the album, which I see features all the Traffic musicians, plus a few others, though the likes of Winwood and Wood don’t appear on all the tracks. When I gave it a listen, however, I was unimpressed. And the problem lies, I think, in the songs themselves. Clearly Capaldi needed Winwood as a co-songwriter. I found the lyrics particularly uninspired, and Capaldi’s vocals nowhere near as good as Winwood or Mason’s. The album does, however, feature great snaps of the lands in action, or in the case of Rebop, seemingly taking a nap.

One has to sympathise with Capaldi. He was in the company of some of the greatest talents of the era, and as a songwriter was simply not as original and exciting as them. The album is formulaic and, frankly, a trifle embarrassing. It probably did Capaldi no favours to reproduce the lyrics on the rear sleeve of this gatefold cover, because it is here that the greatest flaws lie. Even the titles are weak, like Last Day Of Dawn. It’s meaningless. “On the last day of dawn when the world is no more / And the last tiny pigeon’s been swept off the floor …” I can’t go on. One song with redeeming features is Don’t Be A Hero. While naively written, at least here Capaldi takes a firm stab at the dangers of drug abuse – but compared with a song like Neil Young’s The Needle And The Damage Done, this palls. Chris Wood tries to salvage something on How Much Can A Man Really Take with his flute, and there is a reasonably good jam near the end, but all too often Capaldi’s over-lengthy lyrics intrude. Isn’t it significant that the shortest song, lyrics-wise, is the title track, an S Chaplin/A Jolson composition. But it too fails to set the album alight.

I know that Steve Winwood went on to have a long solo career, but he did it without my support. I lost interest in Traffic and its components around the time of Low Spark and Shoot Out, though they did splutter on a trifle longer. Wikipedia says the band released Eagle Flies in 1974 with new bassist Roskoo Gee, but then disbanded. Two compilations, Heavy Traffic and More Heavy Traffic followed. Capaldi and Winwood reunited as Traffic in 1994 for a one-off tour, Wikipedia tells us, and released a CD, Far From Home. But there was no Chris Wood around, because he died of alcohol-related causes in 1983. Fittingly, however, given those heady first few years, Traffic were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2004. And any hopes of further reunions were dashed with the death of Capaldi in 2005, aged 60.

Given how short, but incredibly productive, Traffic’s campaign was, it is worth recording, again thanks to a “trivia” insert on Wikipedia, what a pivotal role three band members played on that classic Jimi Hendrix double album, Electric Ladyland. With Winwood and Mason both friends of the guitarist, Winwood played organ on the slower jam version of Voodoo Chile, while Mason played 12-strong guitar on All Along The Watchtower on the same album. Wikipedia says Hendrix first heard Dylan’s original version of this song, from the album John Wesley Harding, at a party he was invite to by Mason, and decided to do cover it that same night. Also contributing on Electric Ladyland was Chris Wood, whose flute can be heard on 1983 (A Merman I Should Turn To Be).

With such close ties to arguably one of the greatest rock musicians and composers of the era, is it any wonder that the original Traffic were right up there with the best during the pivotal years around 1970, when rock music became the very air that we, the youth, breathed.

No comments:

Post a Comment